|

Dr. John T. McDonald |

|

Dr. McDonald is photographed in the rugged countryside where he spent many years caring for his patients.

|

|

Old newspaper articles are wonderful

sources for some great stories. Such is the case with the following

story that Iíve taken from an article saved by Mrs. Leona Averitt

printed in the July 31, 1991, issue of The Livingston Enterprise.

It was first published in The Nashville Tennessean magazine

section on June 6, 1948. That article was written by Mrs. Celia Cullom,

who, at that time, was the wife of Charles Cullom, a former mayor of

Livingston. He served the town during the years 1948-1951. Here is Mrs.

Cullomís story titled "An Unhurried Man."

Dr. John T. McDonald, a big, patient man of 80 who has been the only doctor in Alpine, Tennessee, for 53 years, probably would have got along famously with Henry Thoreau who once wrote a sharp line about those who "betray too green an interest" in their fates. Dr. McDonald stands out as an unhurried man in a community where things happen slowly. Not until seven years ago did the doctor have a telephone in his farm home. When he got one, it was a community gift. He didnít own a car until 1942, and his neighbors were responsible for it too. He is reluctant to accept payment for his services. His patients learned long ago that the only way they could settle their bills was to mail the doctor their money. "Some other time," he tells those who try to pay him personally. "No hurry. Some other time." A friends once tried to have a heart-to-heart talk with him about the uses of currency. "Money?" the doctor said. "Why, all a man needs is enough to get along on." Patients have settled their debts in wheat, rye, potatoes, hams, milk. His refusal to keep books or to send out statements sometimes brings him surprises. Not long ago, a patient whom he hadnít seen in years appeared to pay him for medical services rendered 18 years before. Dr. McDonald is a large, craggy man, who was born in 1868 in Alpine and went on from the schools there to become an honor student at the University of Nashville medical school. He was graduated in 1895 and shortly won an invitation to teach there. He refused. Alpine needed him. He turned down an opportunity to do tuberculosis research for the same reason, but after practicing several years, he began to specialize in tubercular cases and gained statewide recognition for himself. While interning at St. Thomas Hospital in Nashville, Dr. McDonald became a Catholic, a faith to which he has clung ever since, in an area where a Catholic is a great rarity. He attends mass in Cookeville, the nearest church. He lives outside the Overton County community of Alpine in a rambling, gray farmhouse on a 150 acre farm which he works "between callers" with the aid of his son, Leeman, who volunteered in World War II in spite of being over age and who was seriously wounded. The newest equipment on his farm pertains to his profession - a highly polished sign - "J. T. McDonald, Medicine and Surgery," and modern medical books in the dining room which is also his office. These days, Mrs. McDonald spends much of her time in this room. She is bedridden with arthritis and her husband, to ease the tedium of her existence, has set up a bed in his office where Mrs. McDonald can rest and talk with whomever he is treating. If the doctor makes a call that takes him far from home, he wonít stay for dinner unless he knows the hostess to be a good cook. Dr. A.B. Qualls of Livingston recalled that he once went to consult with Dr. McDonald at an isolated farm. The latter met him at the gate. "They asked us to stay for dinner, but Iíve told them youíre very peculiar about not wanting to eat away from home. I said we couldnít stay. Now you back me up." "I had a ravenous appetite, but I backed him up," the Livingston doctor reported. McDonaldís usual habit, if he does take dinner with a patientís family, is to make a simple announcement to the head of the house. "Iíll have chicken for supper tonight," he says. Then, he walks briskly to the chicken yard, selects a likely candidate, and pointing to avoid any possible error, declares, "Iíll have that hen right there." He has yet to make an unwise choice, say those who know him. The Catholic doctor and the minister of the Presbyterian church of Alpine, the Rev. Bernard Taylor, have been close friends a long time. Until 1941, the minister continually beat a path over the three miles separating his home from the McDonald farm, relaying telephone messages to the doctor, who had no telephone. Late in the fall of 1941, about Thanksgiving time, a friend of Taylorís who knew about the ministerís activities as courier, suggested that a home telephone line be strung from the Taylor house to the doctorís. The communication link was everybodyís business. The right-of-way for the telephone poles was secured within a week. The doctorís neighbors strung the wires. In two weeks, Dr. McDonald was within the reach of anyone who could hold a telephone receiver. The Taylors remain a vital party of the relay system, however, since they had to answer the calls initially. Dr. McDonald inspires confidence in his patients, no less than a half century of practice makes him seem practically immortal than that he is always available. He may appear, after a hurry-up call, with his glasses stuck carelessly on his large nose and his suspenders buttoned in haste, but his step is sure and steady. Although he is reluctant to admit that chronological old age has overtaken him, he has been known to use his impressive years to discipline a frightened patient. He told one nervous man, "Now, Ed, if we both tremble at the same time, weíll never get anywhere." If he feels that he cannot deal with the ramifications of a specific case, he says so. Then, he takes the patient to a medical center himself, usually to Nashville, and stands by with his moral support while better equipped doctors attend the case. Six years ago, the community found a way to repay Dr. McDonald. Until the doctor was past 50, he rode an old bay horse on his daily circuit of calls. When he abandoned his horse - or, as he says, the horse abandoned him - he either walked to a patientís home or some relatives of the latter called for him. A broken hip in 1940 put him to bed for several months, and he never quite regained his old pace. Some time later, Taylor and Jim Allred of Livingston, another of the doctorís cronies, began sounding out the community about giving the doctor a car. Alpine is a town of 200 souls and few of them are considered rich, but more than 1,000 persons in the community gave money to buy him a car. He was invited to choose the make and model himself in Nashville. On a cold, blustery day in January, 1942, Dr. McDonald, Jim Allred, and the Rev. and Mrs. Bernard Taylor, got into Taylorís car and made the trip to Nashville over roads deep in snow. Most of the display rooms in the city were closed, but the doctor went window shopping. He made his choice, a Chrysler, without even sitting the front seat of the vehicle. The salesman said he was sorry the weather was so bad, otherwise, he would be delighted to take them all for a trial drive. The doctor said the new car looked good to him, and heís take it. Prudently, however, he took down the salesmanís address. He never learned to drive the car, somehow, he got the brake and the accelerator confused. Today, his son drives him, and before that, patients or their relatives drove. The doctor never made an acceptance speech when he got back home in the new car. He couldnít trust himself to get through one. And he still gets a little choked up when he thinks about it. Dr. McDonald treated many Fentress county patients, especially those who lived near the Overton-Fentress county line. I was a school mate of Dr. McDonaldís only daughter, Edith. We attended Stockton Valley Baptist Academy at Helena, Tennessee in the 1920's. Edith and I were boarding students in the dormitory at that time. She died rather young. I was fortunate to have met, through Edithís friendship, her father, Dr. McDonald. Dr. McDonald and Mrs. Leona Averittís mother, Mrs. Myrtle McDonald (whose maiden name was also McDonald), were first cousins. Mrs. Myrtle McDonald was the wife of John Allen McDonald. Thank you, Leona, for sharing this story with me. |

|

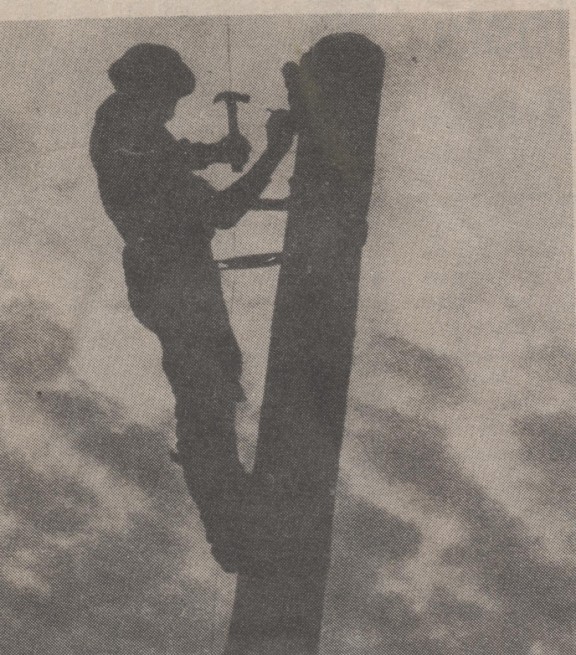

A Phone For The Doctor. W.H. Mullins of Alpine worked to string a telephone line to the home of Dr. McDonald. The community worked together to provide the doctor with a telephone.

|

|

House Call - Drew and Granville Ledbetter drove Dr. McDonald back from a patientís home high on King Mountain. It was 1942 before the doctor owned a car which was provided by about 1,000 people who gave money for the purchase of a vehicle.

|