|

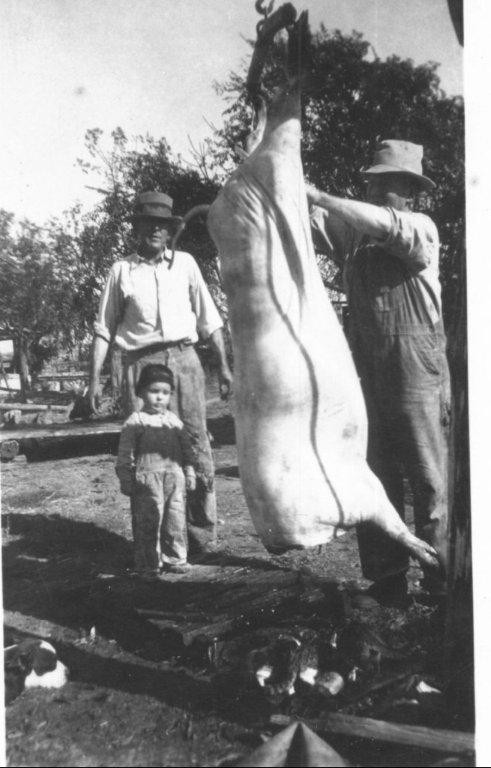

Hog Killing Time on the Qualls Farm

|

|

Carolyn Qualls White along with her sister, Gail Qualls Walker, were photographed with their grandparents, Luther Qualls and wife Eura Qualls on the Qualls farm just outside of Livingston.

|

|

Carolyn Qualls White was kind enough to

share her memories of a ritual that was included in most farm families

who live in this area. She describes in detail just how hog killing

time was done on her family farm, something she wanted to preserve in

writing for her children and grandchildren. Carolyn’s grandparents were

Luther and Eura Qualls, and her parents were Gentry and Talmadge

Qualls. The Qualls farm is located just outside the Livingston city

limits on Highway 52. Both Carolyn and her sister, Gail Qualls Walker,

continue to live on the family farm. Here are Carolyn’s memories:

“When I was about nine or ten years old,

one of the times I most looked forward to was hog killing. I realize

now that my parents and grandparents did not share my enthusiasm for

this nasty job that took place very year, usually between Thanksgiving

and Christmas. “When the first good cold spell comes,” Grandpa would

say. He would start listening to the weather reports on the radio and

also would fine-turn his own personal weather forecasting. My mother

and grandmother would start making sausage sacks a week or so ahead of

time. These sacks (small cloth bags about four or five inches across

and about fifteen inches long) were used to put fresh ground seasoned

sausage in and would then be hung in the smokehouse for the length of

time it took to properly smoke and cure. My daddy and grandpa were the

overseerers of this project, and I could hardly wait until it was ready

for the frying pan. It is still my favorite cured meat today. Ham runs

a close second.

“When the cold snap came that promised to

last two or three days, things started to happen. Knives came out of

hiding places that even I didn’t know about. They were used only for

this procedure and were honed to an edge that made all the womenfolk

jumpy and nervous about using them. My sister and I were warned

repeatedly about them. The scalding pan was cleaned and readied. The

kitchen table and cabinets tops were scrubbed down. The morning would

come when Daddy would say, “Well, girls, you had better get off the bus

at Pa and Granny’s house this afternoon. We are going to kill hogs.”

|

|

|

|

“This annual event always took place at my

grandparents’ house, as their kitchen was larger than ours. We all

lived on the same farm; our house was a short distance from theirs. I

spent a lot of time running back and forth between the two places when I

was growing up.

“When I would hear that announcement from

Daddy, the school day ahead did not seem so long and boring. I could

not wait to get off the bus at my grandparents. It gave me a smug

feeling, knowing that everyone else on the bus would know that something

out of the ordinary was happening at the Qualls’ place, and only my

sister and I knew what it was. We would enter the “front room” that was

kept warm by a coal burning fireplace. To get to the kitchen where all

the activity was taking place, you had to go through either an icy

bedroom or an equally icy dining room. Once in the kitchen, the sights

and smells were a little overwhelming. The whole kitchen had been

turned into a butcher shop. The large table was covered with containers

of pork in various stages of preparation. There would be sides of ribs,

the sides from which the bacon was cut, shoulder, hams, and some scrap

pieces that were carefully looked over and cut up for the sausage

grinder. Then there were the large dishpans filled with fat that my

sister and I were allowed to cut into small pieces for the lard kettle.

“My first order of business after coming

in from school was to check out the dinner left-overs on the wood cook

stove. (Dinner was at noon, supper was served in the evening.) There

would always be a pan of baked ribs, stewed back-bones with potatoes,

beans, and various other vegetables. After I had gorged myself on

“left-overs,” I would try to get a seat at the table by my great-aunt

Eula. She always wanted to be in on the hog killing. She was there

many years that I remember. Aunt Eula was deaf as a post, and a kinder,

sweeter soul never lived. She had a love for people, and always came

when there was a need. I suppose she thought her little sister, my

grandmother, needed all the help she could get at this time. She could

hear only if you shouted in her ear, and sometimes only nodded and

smiled if she didn’t understand your shout. Her most admirable quality

to me was that she could burp like no one I had ever heard. It was

truly outstanding. With her lack of hearing, she had no idea of the

volume of her efforts. She could put most men to shame. I tried so

hard to burp like Aunt Eula and failed miserably, much to my mother’s

relief.

“As the afternoon wore on, Daddy would

take what was to be ground into sausage to a grocery in town where he

worked in the winter months and Saturdays year around. The owners were

family friends and he was welcome to grind the sausage there. He would

return with large dishpans full of ground unseasoned sausage. After

the supper dishes had been cleared away, working up the sausage would

begin. I always watched, not wanting to get in that greasy mess up to

my elbows just to stir in the seasoning. It was more fun to watch the

grown-ups. One time Grandpa’s pipe dropped from his mouth and scattered

a small amount of Country Gentleman tobacco in the mixture. Of course

it didn’t take much doing to get it out, but it was a bit upsetting to

my Grandmother, and she had few curt remarks for Grandpa about his

carelessness.

“After the sausage was stuffed into the

sacks for smoking, another batch was refrigerated to begin frying for

the canned sausage. This was usually done the second day. By this

time, everyone was exhausted and ready for a good night’s sleep.

Sometimes we stayed all night at Pa and Granny’s since no one had been

at our house that day to keep a fire going and the house would be very

hard to heat.

“We would wake up the next morning to a

breakfast of tenderloin, biscuits and gravy. The canned sausage frying

would begin that day as well as the lard rendering and cleaning the

hog’s heads for souse (pressed meat). Usually by the third day, things

were getting back to normal; the doorknobs were wiped free of grease and

stayed that way, and we would be staying nights back in our house.

“The holidays were just around the corner

and we had all kinds of fresh meat, but we always had turkey and

dressing for Christmas dinner. Hogs were fairly cheap in that day and

time and were used for family food. Cattle were for market, and it was

rare to hear that a neighbor had killed a beef to eat. Besides, very

few people had deep freezers in their homes to keep it. In today’s

health conscious world, I can’t help thinking back about all that pork

everyone ate. The word “cholesterol” had not been coined in the late

forties and early fifties, at least not in rural middle Tennessee. It

would not have had time to jell in anyone’s arteries with the physical

activity involved in everyday living.

“There were innumerable tasks associated

with hog killing time, and being the age I was, I only looked on it as a

very good time with my family. These hard, thankless jobs were a way of

life to all people who lived on a farm, and you just did what you had to

do, not thinking of the drudgery involved. I am grateful that these

tasks were carried out with good natured relatives who went about their

work without complaint. This is what has made good memories of loving

parents and grandparents that I still miss.”

|